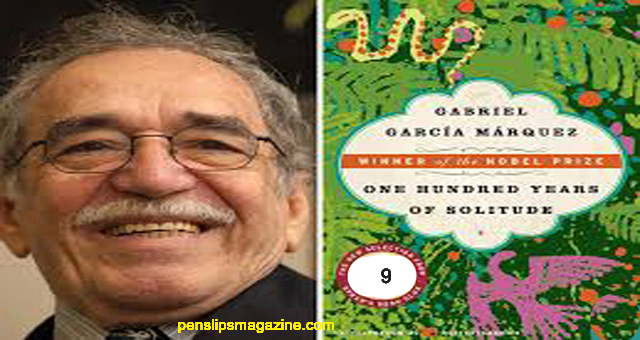

One Hundred Years of Solitude … Garcia Marquez

GABRIEL GARCIA MARQUEZ was born in Aracataca, Colombia in 1928, but he lived most of his life in Mexico and Europe. He attended the University of Bogota and later worked as staff reporter and film critic for the Colombian newspaper El Espectador. In addition to ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE, he has also written two collections of short fiction, NO ONE WRITES TO THE COLONEL and LEAF STORM. Penslips Magazine intends to present this novel regularly.

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

TRANSLATED FROM THE SPANISH

BY GREGORY RABASSA

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

CHARACTERS

Jort Areadio BoendUi

m. Cnula Iguarln , olonel Aurellano Btiendia-,

-Jos6 Areadio

m-Rebeca , m. Remcdios Moscote. Remcdios Moscote , Aurcliano

NINE

Chapter 2

Ursula was still a virgin a year after her marriage because her husband was impotent. Jose Arcadio

Buendia was the last one to hear the mmor.

“Look at what people are going around saying, Ursula,” he told his wife very calmly.

“Let them talk,” she said. “We know that it’s not true.”

So the situation went on the same way for another six months until that tragic Sunday when Jose

Arcadio Buendia won a cockfight from Prudencio Aguilar. Furious, aroused by the blood of his bird,

the loser backed away from Jose Arcadio Buendia so that everyone in the cockpit could hear what

he was going to tell him.

“Congratulations!” he shouted. “Maybe that rooster of yours can do your wife a favor.”

Jose Arcadio Buendia serenely picked up his rooster. “I’ll be right back,” he told everyone. And

then to Prudencio Aguilar:

“You go home and get a weapon, because I’m going to kill you.”

Ten minutes later he returned with the notched spear that had belonged to his grandfather. At

the door to the cockpit, where half the town had gathered, Prudencio Aguilar was waiting for him.

There was no time to defend himself. Jose Arcadio Buendia’s spear, thrown with the strength of a

bull and with the same good aim with which the first Aureliano Buendia had exterminated the

jaguars in the region, pierced his throat. That night, as they held a wake over the corpse in the

cockpit, Jose Arcadio Buendia went into the bedroom as his wife was putting on her chastity pants.

Pointing the spear at her he ordered: “Take them off.” Ursula had no doubt about her husband’s

decision. “You’ll be responsible for what happens,” she murmured. Jose Arcadio Buendia stuck the

spear into the dirt floor.

“If you bear iguanas, we’ll raise iguanas,” he said. “But there’ll be no more killings in this town

because of you.”

It was a fine June night, cool and with a moon, and they were awake and frolicking in bed until

dawn, indifferent to the breeze that passed through the bedroom, loaded with the weeping of

Pmdencio Aguilar’s kin.

The matter was put down as a duel of honor, but both of them were left with a twinge in their

conscience. One night, when she could not sleep, Ursula went out into the courtyard to get some

water and she saw Prudencio Aguilar by the water jar. He was livid, a sad expression on his face,

trying to cover the hole in his throat with a plug made of esparto grass. It did not bring on fear in

her, but pity. She went back to the room and told her husband what she had seen, but he did not

think much of it. “This just means that we can’t stand the weight of our conscience.” Two nights

later Ursula saw Prudencio Aguilar again, in the bathroom, using the esparto plug to wash the

clotted blood from his throat. On another night she saw him strolling in the rain. Jose Arcadio

Buendia, annoyed by his wife’s hallucinations, went out into the courtyard armed with the spear.

There was the dead man with his sad expression.

“You go to hell,” Jose Arcadio Buendia shouted at him. “Just as many times as you come back,

I’ll kill you again.”

Pmdencio Aguilar did not go away, nor did Jose Arcadio Buendia dare throw the spear. He never

slept well after that. He was tormented by the immense desolation with which the dead man had

looked at him through the rain, his deep nostalgia as he yearned for living people, the anxiety with

which he searched through the house looking for some water with which to soak his esparto plug.

“He must be suffering a great deal,” he said to Ursula. “You can see that he’s so very lonely.” She

was so moved that the next time she saw the dead man uncovering the pots on the stove she

understood what he was looking for, and from then on she placed water jugs all about the house.

One night when he found him washing his wound in his own room, Jose Anedio Buendia could no

longer resist.