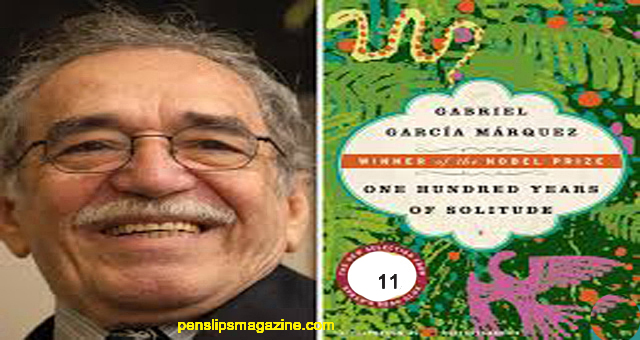

One Hundred Years of Solitude … Garcia Marquez

GABRIEL GARCIA MARQUEZ was born in Aracataca, Colombia in 1928, but he lived most of his life in Mexico and Europe. He attended the University of Bogota and later worked as staff reporter and film critic for the Colombian newspaper El Espectador. In addition to ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE, he has also written two collections of short fiction, NO ONE WRITES TO THE COLONEL and LEAF STORM. Penslips Magazine intends to present this novel regularly.

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

TRANSLATED FROM THE SPANISH

BY GREGORY RABASSA

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

CHARACTERS

Jort Areadio BoendUi

m. Cnula Iguarln , olonel Aurellano Btiendia-,

-Jos6 Areadio

m-Rebeca , m. Remcdios Moscote. Remcdios Moscote , Aurcliano

ELEVEN

Chapter 2

Around that time a merry, foul-mouthed, provocative woman came to the house to help with the

chorea, and she knew how to read the future in cards. Ursula spoke to her about her son. She

thought that his disproportionate size was something as unnatural as her cousin’s tail of a pig.

The woman let out an expansive laugh that resounded through the house like a spray of broken

glass. “Just the opposite,” she said. “He’ll be very lucky.” In order to confirm her prediction she

brought her cards to the house a few days later and locked herself up with Jose Arcadio in a granary

off the kitchen. She calmly placed her cards on an old carpenter’s bench, saying anything that came

into her head, while the boy waited beside her, more bored than intrigued. Suddenly she reached out

her hand and touched him. “Lordy!” she said, sincerely startled, and that was all she could say. Jose

Arcadio felt his bones filling up with foam, a languid fear, and a terrible desire to weep. The woman

made no insinuations. But Jose Arcadio kept looking for her all night long, for the smell of smoke

that she had under her armpits and that had got caught under his skin. He wanted to be with her all

the time, he wanted her to be his mother, for them never to leave the granary, and for her to say

“Lordy!” to him. One day he could not stand it any more and. he went looking for her at her house:

He made a formal visit, sitting uncomprehendingly in the living room without saying a word. At

that moment he had no desire for her. He found her different, entirely foreign to the image that her

smell brought on, as if she were someone else. He drank his coffee and left the house in depression.

That night, during the frightful time of lying awake, he desired her again with a brutal anxiety, but he

did not want her that time as she had been in the granary but as she had been that afternoon.

Days later the woman suddenly called him to her house, where she was alone with her mother,

and she had him come into the bedroom with the pretext of showing him a deck of cards. Then

she touched him with such freedom that he suffered a delusion after the initial shudder, and he felt

more fear than pleasure. She asked him to come and see her that night. He agreed, in order to get

away, knowing that he was incapable of going. But that night, in his burning bed, he understood that

he had to go we her, even if he were not capable. He got dressed by feel, listening in the dark to his

brother’s calm breathing, the dry cough of his father in the next room, the asthma of the hens in the

courtyard, the buzz of the mosquitoes, the beating of his heart, and the inordinate bustle of a world

that he had not noticed until then, and he went out into the sleeping street. With all his heart he

wanted the door to be barred and not just closed as she had promised him. But it was open. He

pushed it with the tips of his fingers and the hinges yielded with a mournful and articulate moan that

left a frozen echo inside of him. From the moment he entered, sideways and trying not to make a

noise, he caught the smell. He was still in the hallway, where the woman’s three brothers had their

hammocks in positions that he could not see and that he could not determine in the darkness as he

felt his way along the hall to push open the bedroom door and get his bearings there so as not to

mistake the bed. He found it. He bumped against the ropes of the hammocks, which were lower

than he had suspected, and a man who had been snoring until then turned in his sleep and said in a

kind of delusion, “It was Wednesday.” When he pushed open the bedroom door, he could not

prevent it from scraping against the uneven floor. Suddenly, in the absolute darkness, he understood

with a hopeless nostalgia that he was completely disoriented. Sleeping in the narrow room were the

mother, another daughter with her husband and two children, and the woman, who may not have

been there. He could have guided himself by the smell if the smell had not been all over the house,

so devious and at the same time so definite, as it had always been on his skin. He did not move for a

long time, wondering in fright how he had ever got to that abyss of abandonment, when a hand with

all its fingers extended and feeling about in the darkness touched his face. He was not surprised, for

without knowing, he had been expecting it. Then he gave himself over to that hand, and in a terrible

state of exhaustion he let himself be led to a shapeless place where his clothes were taken off and he