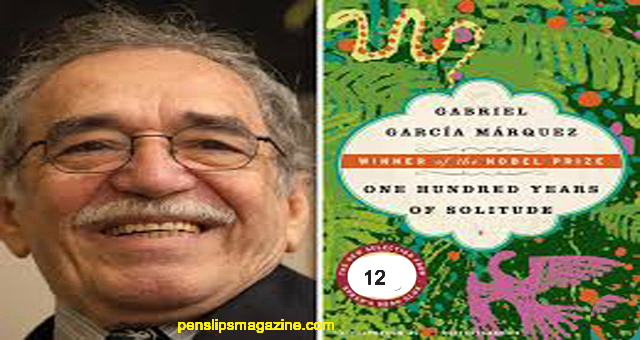

One Hundred Years of Solitude … Garcia Marquez

GABRIEL GARCIA MARQUEZ was born in Aracataca, Colombia in 1928, but he lived most of his life in Mexico and Europe. He attended the University of Bogota and later worked as staff reporter and film critic for the Colombian newspaper El Espectador. In addition to ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE, he has also written two collections of short fiction, NO ONE WRITES TO THE COLONEL and LEAF STORM. Penslips Magazine intends to present this novel regularly.

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

TRANSLATED FROM THE SPANISH

BY GREGORY RABASSA

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

CHARACTERS

Jort Areadio BoendUi

m. Cnula Iguarln , olonel Aurellano Btiendia-,

-Jos6 Areadio

m-Rebeca , m. Remcdios Moscote. Remcdios Moscote , Aurcliano

12

Chapter 2

Then he gave himself over to that hand, and in a terrible

state of exhaustion he let himself be led to a shapeless place where his clothes were taken off and he

was heaved about like a sack of potatoes and thrown from one side to the other in a bottomless

darkness in which Inis arms were useless, where it no longer smelled of woman but of ammonia, and

where he tried to remember her face and found before him the face of Ursula, confusedly aware that

he was doing something that for a very long time he had wanted to do but that he had imagined

could really never be done, not knowing what he was doing because he did not know where his feet

were or where Inis head was, or whose feet or whose head, and feeling that he could no longer resist

the glacial rumbling of his kidneys and the air of his intestines, and fear, and the bewildered anxiety

to flee and at the same time stay forever in that exasperated silence and that fearful solitude.

Her name was Pilar Ternera. She had been part of the exodus that ended with the founding of

Macondo, dragged along by her family in order to separate her from the man who had raped her at

fourteen and had continued to love her until she was twenty-two, but who never made up his mind

to make the situation public because he was a man apart. He promised to follow her to the ends of

the earth, but only later on, when he put his affairs in order, and she had become tired of waiting for

him, always identifying him with the tall and short, blond and bmnet men that her cards promised

from land and sea within three days, three months, or three years. With her waiting she had lost the

strength of her thighs, the firmness of her breasts, her habit of tenderness, but she kept the madness

of her heart intact. Maddened by that prodigious plaything, Jose Arcadio followed her path every

night through the labyrinth of the room. On a certain occasion he found the door barred, and he

knocked several times, knowing that if he had the boldness to knock the first time he would have

had to knock until the last, and after an interminable wait she opened the door for him. During the

day, lying down to dream, he would secretly enjoy the memories of the night before. But when she

came into the house, merry, indifferent, chatty, he did not have to make any effort to hide his

tension, because that woman, whose explosive laugh frightened off the doves, had nothing to do

with the invisible power that taught him how to breathe from within and control his heartbeats, and

that had permitted him to understand why man are afraid of death. He was so wrapped up in

himself that he did not even understand the joy of everyone when his father and his brother aroused

the household with the news that they had succeeded in penetrating the metallic debris and had

separated Ursula’s gold.

They had succeeded, as a matter of fact, after putting in complicated and persevering days at it.

Ursula was happy, and she even gave thanks to God for the invention of alchemy, while the people

of the village cmshed into the laboratory, and they served them guava jelly on crackers to celebrate

the wonder, and Jose Arcadio Buendia let them see the cmcible with the recovered gold, as if he had

just invented it. Showing it all around, he ended up in front of his older son, who during the past

few days had barely put in an appearance in the laboratory. He put the dry and yellowish mass in

front of his eyes and asked him: “What does it look like to you?” Jose Arcadio answered sincerely:

“Dog shit.”

His father gave him a blow with the back of his hand that brought out blood and tears. That

night Pilar Ternera put arnica compresses on the swelling, feeling about for the bottle and cotton in

the dark, and she did everything she wanted with him as long as it did not bother him, making an

effort to love him without hurting him. They reached such a state of intimacy that later, without

realizing it, they were whispering to each other.

“I want to be alone with you,” he said. “One of these days I’m going to tell everybody and we

can stop all of this sneaking around.”

She did not try to calm him down.

“That would be fine,” she said “If we’re alone, we’ll leave the lamp lighted so that we can see

each other, and I can holler as much as I want without anybody’s having to butt in, and you can

whisper in my ear any crap you can think of.”