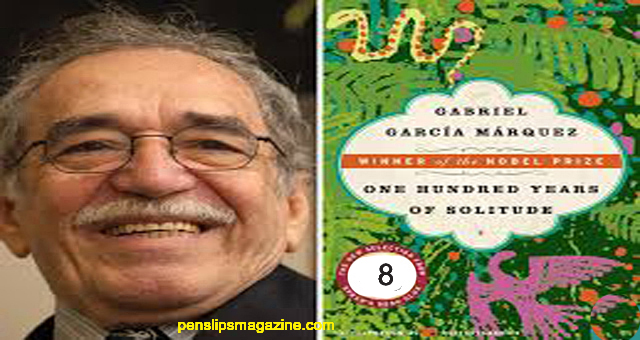

One Hundred Years of Solitude … Garcia Marquez

GABRIEL GARCIA MARQUEZ was born in Aracataca, Colombia in 1928, but he lived most of his life in Mexico and Europe. He attended the University of Bogota and later worked as staff reporter and film critic for the Colombian newspaper El Espectador. In addition to ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE, he has also written two collections of short fiction, NO ONE WRITES TO THE COLONEL and LEAF STORM. Penslips Magazine intends to present this novel regularly.

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

TRANSLATED FROM THE SPANISH

BY GREGORY RABASSA

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

CHARACTERS

Jort Areadio BoendUi

m. Cnula Iguarln , olonel Aurellano Btiendia-,

-Jos6 Areadio

m-Rebeca , m. Remcdios Moscote. Remcdios Moscote , Aurcliano

EIGHT

Chapter 2

WHEN THE PIRATE Sir Francis Drake attacked Riohacha in the sixteenth century, Ursula Iguaran’s

great-great-grandmother became so frightened with the ringing of alarm bells and the firing of

cannons that she lost control of her nerves and sat down on a lighted stove. The burns changed her

into a useless wife for the rest of her days. She could only sit on one side, cushioned by pillows, and

something strange must have happened to her way of walking, for she never walked again in public.

She gave up all kinds of social activity, obsessed with the notion that her body gave off a singed

odor. Dawn would find her in the courtyard, for she did not dare fall asleep lest she dream of the

English and their ferocious attack dogs as they came through the windows of her bedroom to

submit her to shameful tortures with their red-hot irons. Her husband, an Aragonese merchant by

whom she had two children, spent half the value of his store on medicines and pastimes in an

attempt to alleviate her terror. Finally he sold the business and took the family to live far from the

sea in a settlement of peaceful Indians located in the foothills, where he built his wife a bedroom

without windows so that the pirates of her dream would have no way to get in.

In that hidden village there was a native-born tobacco planter who had lived there for some time,

Don Jose Arcadio Buendfa, with whom Ursula’s great-great-grandfather established a partnership

that was so lucrative that within a few years they made a fortune. Several centuries later the great-

great-grandson of the native-born planter married the great-great-granddaughter of the Aragonese.

Therefore, every time that Ursula became exercised over her husband’s mad ideas, she would leap

back over three hundred years of fate and curse the day that Sir Francis Drake had attacked

Riohacha. It was simply a way. of giving herself some relief, because actually they were joined till

death by a bond that was more solid that love: a common prick of conscience. They were cousins.

They had grown up together in the old village that both of their ancestors, with their work and their

good habits, had transformed into one of the finest towns in the province. Although their marriage

was predicted from the time they had come into the world, when they expressed their desire to be

married their own relatives tried to stop it. They were afraid that those two healthy products of two

races that had interbred over the centuries would suffer the shame of breeding iguanas. There had

already been a horrible precedent. An aunt of Ursula’s, married to an uncle of Jose Arcadio Buendfa,

had a son who went through life wearing loose, baggy trousers and who bled to death after having

lived forty-two years in the purest state of virginity, for he had been born and had grown up with a

cartilaginous tail in the shape of a corkscrew and with a small tuft of hair on the tip. A pig’s tail that

was never allowed to be seen by any woman and that cost him his life when a butcher friend did him

the favor of chopping it off with his cleaver. Jose Arcadio Buendfa, with the whimsy of his nineteen

years, resolved the problem with a single phrase: “I don’t care if I have piglets as long as they can

talk.” So they were married amidst a festival of fireworks and a brass band that went on for three

days. They would have been happy from then on if Ursula’s mother had not terrified her with all

manner of sinister predictions about their offspring, even to the extreme of advising her to refuse to

consummate the marriage. Fearing that her stout and willful husband would rape her while she slept,

Ursula, before going to bed, would put on a rudimentary kind of drawers that her mother had made

out of sailcloth and had reinforced with a system of crisscrossed leather straps and that was closed in

the front by a thick iron buckle. That was how they lived for several months. During the day he

would take care of his fighting cocks and she would do frame embroidery with her mother. At night

they would wrestle for several hours in an anguished violence that seemed to be a substitute for the

act of love, until popular intuition got a whiff of something irregular and the memoir spread۔