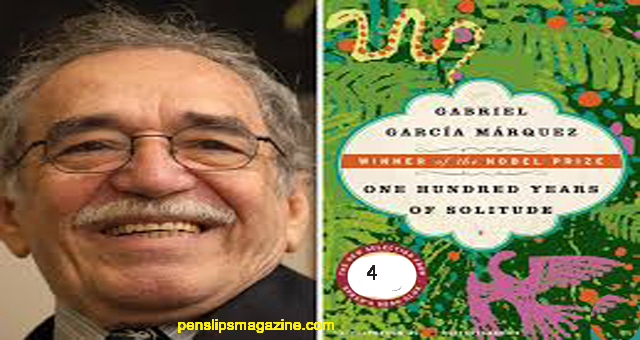

One Hundred Years of Solitude … Garcia Marquez

GABRIEL GARCIA MARQUEZ was born in Aracataca, Colombia in 1928, but he lived most of his life in Mexico and Europe. He attended the University of Bogota and later worked as staff reporter and film critic for the Colombian newspaper El Espectador. In addition to ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE, he has also written two collections of short fiction, NO ONE WRITES TO THE COLONEL and LEAF STORM. Penslips Magazine intends to present this novel regularly.

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

TRANSLATED FROM THE SPANISH

BY GREGORY RABASSA

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

CHARACTERS

Jort Areadio BoendUi

m. Cnula Iguarln , olonel Aurellano Btiendia-,

-Jos6 Areadio

m-Rebeca , m. Remcdios Moscote. Remcdios Moscote , Aurcliano Jose ,

FOUR

That spirit of social initiative disappeared in a short time, pulled away by the fever of the

magnets, the astronomical calculations, the dreams of transmutation, and the urge to discover the

wonders of the world. From a clean and active man, Jose Arcadio Buendia changed into a man lazy

in appearance, careless in his dress, with a wild beard that Ursula managed to trim with great effort

and a kitchen knife. There were many who considered him the victim of some strange spell. But

even those most convinced of his madness left work and family to follow him when he brought out

his tools to clear the land and asked the assembled group to open a way that would put Macondo in

contact with the great inventions.

Jose Arcadio Buendia was completely ignorant of the geography of the region. He knew that to

the east there lay an impenetrable mountain chain and that on the other side of the mountains there

was the ardent city of Riohacha, where in times past—according to what he had been told by the

first Aureliano Buendia, his grandfather—Sir Francis Drake had gone crocodile hunting with

cannons and that he repaired hem and stuffed them with straw to bring to Queen Elizabeth. In his

youth, Jose Arcadio Buendia and his men, with wives and children, animals and all kinds of domestic

implements, had crossed the mountains in search of an outlet to the sea, and after twenty-six

months they gave up the expedition and founded Macondo, so they would not have to go back. It

was, therefore, a route that did not interest him, for it could lead only to the past. To the south lay

the swamps, covered with an eternal vegetable scum and the whole vast universe of the great

swamp, which, according to what the gypsies said, had no limits. The great swamp in the west

mingled with a boundless extension of water where there were soft-skinned cetaceans that had the

head and torso of a woman, causing the ruination of sailors with the charm of their extraordinary

breasts. The gypsies sailed along that route for six months before they reached the strip of land over

which the mules that carried the mail passed. According to Jose Arcadio Buendia’s calculations, the

only possibility of contact with civilization lay along the northern route. So he handed out clearing

tools and hunting weapons to the same men who had been with him during the founding of

Macondo. He threw his directional instruments and his maps into a knapsack, and he undertook the

reckless adventure.

During the first days they did not come across any appreciable obstacle. They went down along

the stony bank of the river to the place where years before they had found the soldier’s armor, and

from there they went into the woods along a path between wild orange trees. At the end of the first

week they killed and roasted a deer, but they agreed to eat only half of it and salt the rest for the days

that lay ahead. With that precaution they tried to postpone the necessity of having to eat macaws,

whose blue flesh had a harsh and musky taste. Then, for more than ten days, they did not see the

sun again. The ground became soft and damp, like volcanic ash, and the vegetation was thicker and

thicker, and the cries of the birds and the uproar of the monkeys became more and more remote,

and the world became eternally sad. The men on the expedition felt overwhelmed by their most

ancient memories in that paradise of dampness and silence, going back to before original sin, as their

boots sank into pools of steaming oil and their machetes destroyed bloody lilies and golden salaman¬

ders. For a week, almost without speaking, they went ahead like sleepwalkers through a universe of

grief, lighted only by the tenuous reflection of luminous insects, and their lungs were overwhelmed

by a suffocating smell of blood. They could not return because the strip that they were opening as

they went along would soon close up with a new vegetation that, almost seemed to grow before

their eyes. “It’s all right,” Jose Arcadio Buendia would say. “The main tiling is not to lose our

bearings.” Always following his compass, he kept on guiding his men toward the invisible north so

that they would be able to get out of that enchanted region. It was a thick night, starless, but the

darkness was becoming impregnated with a fresh and clear air. Exhausted by the long crossing, they

hung up their hammocks and slept deeply for the first time in two weeks. When they woke up, with

the sun already high in the sky, they were speechless with fascination. Before them, surrounded by