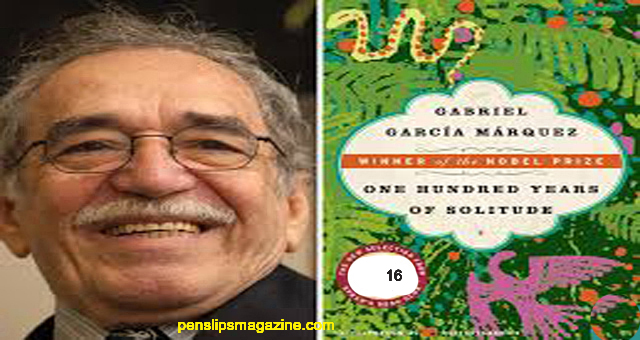

One Hundred Years of Solitude … Garcia Marquez

GABRIEL GARCIA MARQUEZ was born in Aracataca, Colombia in 1928, but he lived most of his life in Mexico and Europe. He attended the University of Bogota and later worked as staff reporter and film critic for the Colombian newspaper El Espectador. In addition to ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE, he has also written two collections of short fiction, NO ONE WRITES TO THE COLONEL and LEAF STORM.

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

Jort Areadio BoendUi

m. Cnula Iguarln

olonel Aurellano Btiendia-

m. Remcdios Moscote

-Jos6 Areadio

m-Rebeca

Aurcliano Jose

(by Pilar Ternera)

17 Aurelianos

R’emedios the Beauty

Areadio

(by Pilar Ternera)

m. Santa Sofia de la Piedad

Aurellano Segundo

m. Fernanda del Carplo

Amaranta

Jose Areadio Segundo

j_Renata

Remedios (Mane)

Aurellano

(by MauHcioBabfionla)

lose Areadio

-..Amaranta

m. Gasti

ranta Orsula

Gaston

Aurellano

(by Aurellano^

Chapter 3

16

PILAR TERNERA’S son was brought to his grand parents’ house two weeks after he was born. Ursula

admitted him gmdgingly, conquered once more by the obstinacy of her husband, who could not

tolerate the idea that an offshoot of his blood should be adrift, but he imposed the condition that

the child should never know his true identity. Although he was given the name Jose Arcadio, they

ended up calling him simply Arcadio so as to avoid confusion. At that time there was so much

activity in the town and so much bustle in the house that the care of the children was relegated to a

secondary level. They were put in the care of Visitacion, a Guajiro Indian woman who had arrived in

town with a brother in flight from a plague of insomnia that had been scourging their tribe for

several years. They were both so docile and willing to help that Ursula took them on to help her

with her household chores. That was how Arcadio and Amaranta came to speak the Guajiro

language before Spanish, and they learned to drink lizard broth and eat spider eggs without Ursula’s

knowing it, for she was too busy with a promising business in candy animals. Macondo had changed.

The people who had come with Ursula spread the news of the good quality of its soil and its

privileged position with respect to the swamp, so that from the narrow village of past times it

changed into an active town with stores and workshops and a permanent commercial route over

which the first Arabs arrived with their baggy pants and rings in their ears, swapping glass beads for

macaws. Jose Arcadio Buendia did not have a moment’s rest. Fascinated by an immediate reality that

came to be more fantastic than the vast universe of his imagination, he lost all interest in the

alchemist’s laboratory, put to rest the material that had become attenuated with months of

manipulation, and went back to being the enterprising man of earlier days when he had decided

upon the layout of the streets and the location of the new houses so that no one would enjoy

privileges that everyone did not have. He acquired such authority among the new arrivals that

foundations were not laid or walls built without his being consulted, and it was decided that he

should be the one in charge of the distribution of the land. When the acrobat gypsies returned, with

their vagabond carnival transformed now into a gigantic organization of games of luck and chance,

they were received with great joy, for it was thought that Jose Arcadio would be coming back with

them. But Jose Arcadio did not return, nor did they come with the snake-man, who, according to

what Ursula thought, was the only one who could tell them about their son, so the gypsies were not

allowed to camp in town or set foot in it in the future, for they were considered the bearers of

concupiscence and perversion. Jose Arcadio Buendia, however, was explicit in maintaining that the

old tribe of Melquiades, who had contributed so much to the growth of the village with his age-old

wisdom and his fabulous inventions, would always find the gates open. But Melquiades’ tribe,

according to what the wanderers said, had been wiped off the face of the earth because they had

gone beyond the limits of human knowledge.

Emancipated for the moment at least from the torment of fantasy, Jose Arcadio Buendia in a

short time set up a system of order and work which allowed for only one bit of license: the freeing

of the birds, which, since the time of the founding, had made time merry with their flutes, and

installing in their place musical clocks in every house. They were wondrous clocks made of carved

wood, which the Arabs had traded for macaws and which Jose Arcadio Buendia had synchronized

with such precision that every half hour the town grew merry with the progressive chords of the

same song until it reached the climax of a noontime that was as exact and unanimous as a complete

waltz. It was also Jose Arcadio Buendia who decided during those years that they should plant

almond trees instead of acacias on the streets, and who discovered, without ever revealing it, a way

to make them live forever. Many years later, when Macondo was a field of wooden houses with zinc

roofs, the broken and dusty almond trees still stood on the oldest streets, although no one knew

who had planted them. While his father was putting the town in order and Inis mother was increasing

their wealth with her marvelous business of candied little roosters and fish, which left the house

twice a day strung along sticks of balsa wood, Aureliano spent interminable hours in the abandoned

laboratory, learning the art of silverwork by his own experimentation. He had shot up so fast that in

a short time the clothing left behind by his brother no longer fit him and he began to wear his

father’s, but Visitacion had to sew pleats in the shirt and darts in the pants, because Aureliano had

not sequined the corpulence of the others. Adolescence had taken away the softness of his voice and

had made him silent and definitely solitary, but, on the other hand, it had restored the intense

expression that he had had in his eyes when he was born. He concentrated so much on his

experiments in silverwork that he scarcely left the laboratory to eat. Worried ever his inner

withdrawal, Jose Arcadio Buendia gave him the keys to the house and a little money, thinking that

perhaps he needed a woman. But Aureliano spent the money on muriatic acid to prepare some aqua

regia and he beautified the keys by plating them with gold. His excesses were hardly comparable to

those of Arcadio and Amaranta, who had already begun to get their second teeth and still went

about all day clutching at the Indians’ cloaks, stubborn in their decision not to speak Spanish but the

Guajiro language. “You shouldn’t complain.” Ursula told her husband. “Children inherit their

parents’ madness.” And as she was lamenting her misfortune, convinced that the wild behavior of

her children was something as fearful as a pig’s tail, Aureliano gave her a look that wrapped her in an

atmosphere of uncertainty.

“Somebody is coming,” he told her.

Ursula, as she did whenever he made a prediction, tried to break it down with her housewifely

logic. It was normal for someone to be coming. Dozens of strangers came through Macondo every

day without arousing suspicion or secret ideas. Nevertheless, beyond all logic, Aureliano was sure of

Iris prediction.

“I don’t know who it will be,” he insisted, “but whoever it is is already on the way.”

That Sunday, in fact, Rebeca arrived. She was only eleven years old. She had made the difficult

trip from Manaure with some hide dealers who had taken on the task of delivering her along with a

letter to Jose Arcadio Buendia, but they could not explain precisely who the person was who had

asked the favor. Her entire baggage consisted of a small trunk, a little rocking chair with small hand-

painted flowers, and a canvas sack which kept making a cloc-cloc-cloc sound, where she carried her

parents’ bones. The letter addressed to Jose Arcadio Buendia was written is very warm terms by

someone who still loved him very much in spite of time and distance, and who felt obliged by a

basic humanitarian feeling to do the charitable thing and send him that poor unsheltered orphan,

who was a second cousin of Ursula’s and consequendy also a relative of Jose Arcadio Buendia,

although farther removed, because she was the daughter of that unforgettable friend Nicanor Ulloa

and his very worthy wife Rebeca Montiel, may God keep them in His holy kingdom, whose remains

the girl was carrying so that they might be given Christian burial. The names mentioned, as well as

the signature on the letter, were perfecdy legible, but neither Jose Arcadio, Buendia nor Ursula

remembered having any relatives with those names, nor did they know anyone by the name of the

sender of the letter, much less the remote village of Manaure. It was impossible to obtain any further

information from the girl. From the moment she arrived she had been sitting in the rocker, sucking

her finger and observing everyone with her large, startled eyes without giving any sign of

understanding what they were asking her. She wore a diagonally striped dress that had been dyed

black, worn by use, and a pair of scaly patent leather boots. Her hair was held behind her ears with

bows of black ribbon. She wore a scapular with the images worn away by sweat, and on her right

wrist the fang of a carnivorous animal mounted on a backing of copper as an amulet against the evil

eye. Her greenish skin, her stomach, round and tense as a drum, revealed poor health and hunger

that were older than she was, but when they gave her something to eat she kept the plate on her

knees without tasting anything. They even began to think that she was a deaf-mute until the Indians

asked her in their language if she wanted some water and she moved her eyes as if she recognized

them and said yes with her head.

They kept her, because there was nothing else they could do. They decided to call her Rebeca,

which according to the letter was her mother’s name, because Aureliano had the patience to read to

her the names of all the saints and he did not get a reaction from any one of them. Since there was

no cemetery in Macondo at that time, for no one had died up till then, they kept the bag of bones to

wait for a worthy place of burial, and for a long time it got in the way everywhere and would be

found where least expected, always with its clucking of a broody hen.