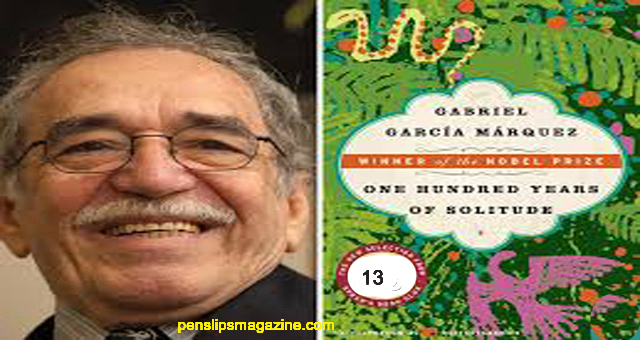

One Hundred Years of Solitude … Garcia Marquez

GABRIEL GARCIA MARQUEZ was born in Aracataca, Colombia in 1928, but he lived most of his life in Mexico and Europe. He attended the University of Bogota and later worked as staff reporter and film critic for the Colombian newspaper El Espectador. In addition to ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE, he has also written two collections of short fiction, NO ONE WRITES TO THE COLONEL and LEAF STORM.

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

TRANSLATED FROM THE SPANISH

BY GREGORY RABASSA

ONE HUNDRED YEARS

OF SOLITUDE

GABRIEL GARCIA MARQUES x ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

Jort Areadio BoendUi

m. Cnula Iguarln

olonel Aurellano Btiendia-

m. Remcdios Moscote

-Jos6 Areadio

m-Rebeca

Aurcliano Jose

(by Pilar Ternera)

17 Aurelianos

R’emedios the Beauty

Areadio

(by Pilar Ternera)

m. Santa Sofia de la Piedad

Aurellano Segundo

m. Fernanda del Carplo

Amaranta

Jose Areadio Segundo

j_Renata

Remedios (Mane)

Aurellano

(by MauHcioBabfionla)

lose Areadio

-..Amaranta

m. Gasti

ranta Orsula

Gaston

Aurellano

(by Aurellano^

Chapter 2

13

That conversation, the biting rancor that he felt against his father, and the imminent possibility of

wild love inspired a serene courage in him. In a spontaneous way, without any preparation, he told

everything to his brother.

At first young Aureliano understood only the risk, the immense possibility of danger that Iris

brother’s adventures implied, and he could not understand the fascination of the subject. Little by

little he became contaminated with the anxiety. He wondered about the details of the dangers, he

identified himself with the suffering and enjoyment of his brother, he felt frightened and happy. He

would stay awake waiting for him until dawn in the solitary bed that seemed to have a bottom of live

coals, and they would keep on talking until it was time to get up, so that both of them soon suffered

from the same drowsiness, felt the same lack of interest in alchemy and the wisdom of their father,

and they took refuge in solitude. “Those kids are out of their heads,” Ursula said. “They must have

worms.” She prepared a repugnant potion for them made out of mashed wormseed, which they

both drank with unforeseen stoicism, and they sat down at the same time on their pots eleven times

in a single day, expelling some rose-colored parasites that they showed to everybody with great

jubilation, for it allowed them to deceive Ursula as to the origin of their distractions and drowsiness.

Aureliano not only understood by then, he also lived his brother’s experiences as something of his

own, for on one occasion when the latter was explaining in great detail the mechanism of love, he

intermpted him to ask: “What does it feel like?” Jose Arcadio gave an immediate reply:

“It’s like an earthquake.”

One January Thursday at two o’clock in the morning, Amaranta was born. Before anyone came

into the room, Ursula examined her carefully. She was light and watery, like a newt, but all of her

parts were human: Aureliano did not notice the new thing except when the house became full of

people. Protected by the confusion, he went off in search of his brother, who had not been in bed

since eleven o’clock, and it was such an impulsive decision that he did not even have time to ask

himself how he could get him out of Pilar Ternera’s bedroom. He circled the house for several

hours, whistling private calls, until the proximity of dawn forced him to go home. In his mother’s

room, playing with the newborn little sister and with a face that drooped with innocence, he found

Jose Arcadio.

Ursula was barely over her forty days’ rest when the gypsies returned. They were the same

acrobats and jugglers that had brought the ice. Unlike Melquiades’ tribe, they had shown very

quickly that they were not heralds of progress but purveyors of amusement. Even when they

brought the ice they did not advertise it for its usefulness in the life of man but as a simple circus

curiosity. This time, along with many other artifices, they brought a flying carpet. But they did not

offer it as a fundamental contribution to the development of transport, rather as an object of

recreation. The people at once dug up their last gold pieces to take advantage of a quick flight over

the houses of the village. Protected by the delightful cover of collective disorder, Jose Arcadio and

Pilar passed many relaxing hours. They were two happy lovers among the crowd, and they even

came to suspect that love could be a feeling that was more relaxing and deep than the happiness,

wild but momentary, of their secret nights. Pilar, however, broke the spell. Stimulated by the

enthusiasm that Jose Arcadio showed in her companionship, she confused the form and the

occasion, and all of a sudden she threw the whole world on top of him. “Now you really are a man,”

she told him. And since he did not understand what she meant, she spelled it out to him.

“You’re going to be a father.”

Jose Arcadio did not dare leave the house for several days. It was enough for him to hear the

rocking laughter of Pilar in the kitchen to run and take refuge in the laboratory, where the artifacts

of alchemy had come alive again with Ursula’s blessing. Jose Arcadio Buendia received his errant son

with joy and initiated him in the search for the philosopher’s stone, which he had finally undertaken.

One afternoon the boys grew enthusiastic over the flying carpet that went swiftly by the laboratory

at window level carrying the gypsy who was driving it and several children from the village who were

merrily waving their hands, but Jose Arcadio Buendia did not even look at it. “Let them dream,” he

said. “We’ll do better flying than they are doing, and with more scientific resources than a miserable

bedspread.” In spite of his feigned interest, Jose Arcadio must understood the powers of the

philosopher’s egg, which to him looked like a poorly blown bottle. He did not succeed in escaping

from his worries. He lost his appetite and he could not sleep. He fell into an ill humor, the same as

his father’s over the failure of his undertakings, and such was his upset that Jose Arcadio Buendia

himself relieved him of his duties in the laboratory, thinking that he had taken alchemy too much to

heart. Aureliano, of course, understood that his brother’s affliction did not have its source in the

search for the philosopher’s stone but he could not get into his confidence. He had lost his former

spontaneity. From an accomplice and a communicative person he had become withdrawn and

hostile. Anxious for solitude, bitten by a vimlent rancor against the world, one night he left his bed

as usual, but he did not go to Pilar Ternera’s house, but to mingle is the tumult of the fair. After

wandering about among all kinds of contraptions with out becoming interested in any of them, he

spotted something that was not a part of it all: a very young gypsy girl, almost a child, who was

weighted down by beads and was the most beautiful woman that Jose Arcadio had ever seen in his

life. She was in the crowd that was witnessing the sad spectacle of the man who had been turned

into a snake for having disobeyed his parents.