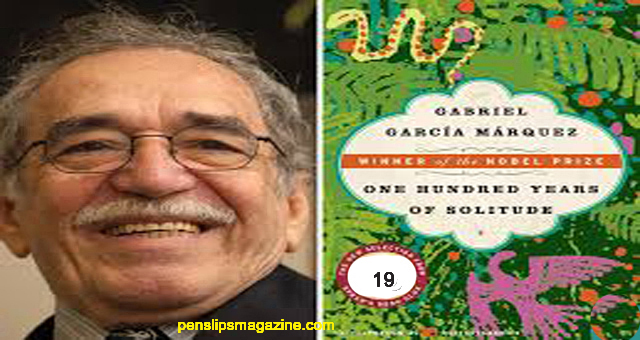

One Hundred Years of Solitude … Garcia Marquez

GABRIEL GARCIA MARQUEZ was born in Aracataca, Colombia in 1928, but he lived most of his life in Mexico and Europe. He attended the University of Bogota and later worked as staff reporter and film critic for the Colombian newspaper El Espectador. In addition to ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE, he has also written two collections of short fiction, NO ONE WRITES TO THE COLONEL and LEAF STORM.

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

Jort Areadio BoendUi

m. Cnula Iguarln

olonel Aurellano Btiendia-

m. Remcdios Moscote

-Jos6 Areadio

m-Rebeca

Aurcliano Jose

(by Pilar Ternera)

17 Aurelianos

R’emedios the Beauty

Areadio

(by Pilar Ternera)

m. Santa Sofia de la Piedad

Aurellano Segundo

m. Fernanda del Carplo

Amaranta

Jose Areadio Segundo

j_Renata

Remedios (Mane)

Aurellano

(by MauHcioBabfionla)

lose Areadio

-..Amaranta

m. Gasti

ranta Orsula

Gaston

Aurellano

(by Aurellano^

Chapter 3

19

When Jose Arcadio Buendia realized that the plague had invaded the town, he gathered together

the heads of families to explain to them what he knew about the sickness of insomnia, and they

agreed on methods to prevent the scourge from spreading to other towns in the swamp. That was

why they took the bells off the goats, bells that the Arabs had swapped them for macaws, and put

them at the entrance to town at the disposal of those who would not listen to the advice and

entreaties of the sentinels and insisted on visiting the town. All strangers who passed through the

streets of Macondo at that time had to ring their bells so that the sick people would know that they

were healthy. They were not allowed to eat or drink anything during their stay, for there was no

doubt but that the illness was transmitted by mouth, and all food and drink had been contaminated

by insomnia. In that way they kept the plague restricted to the perimeter of the town. So effective

was the quarantine that the day came when the emergency situation was accepted as a natural thing

and life was organized in such a way that work picked up its rhythm again and no one worried any

more about the useless habit of sleeping.

It was Aureliano who conceived the formula that was to protect them against loss of memory for

several months. He discovered it by chance. An expert insomniac, having been one of the first, he

had learned the art of silverwork to perfection. One day he was looking for the small anvil that he

used for laminating metals and he could not remember its name. His father told him: “Stake.”

Aureliano wrote the name on a piece of paper that he pasted to the base of the small anvil: stake. In

that way he was sure of not forgetting it in the future. It did not occur to him that this was the first

manifestation of a loss of memory, because the object had a difficult name to remember. But a few

days later be, discovered that he had trouble remembering almost every object in the laboratory.

Then he marked them with their respective names so that all he had to do was read the inscription

in order to identify them. When his father told him about his alarm at having forgotten even the

most impressive happenings of his childhood, Aureliano explained his method to him, and Jose

Arcadio Buendia put it into practice all through the house and later on imposed it on the whole

village. With an inked brush he marked everything with its name: table, chair, clock, door, wall, bed, pan.

He went to the corral and marked the animals and plants: cow, goat, pig, hen, cassava, caladium, banana.

Little by little, studying the infinite possibilities of a loss of memory, he realized that the day might

come when tilings would be recognized by their inscriptions but that no one would remember their

use. Then he was more explicit. The sign that he hung on the neck of the cow was an exemplary

proof of the way in which the inhabitants of Macondo were prepared to fight against loss of

memory: This is the cow. She must be milked every morning so that she will produce milk, and the milk must be

boiled in order to be mixed with coffee to make coffee and milk. Thus they went on living in a reality that was

slipping away, momentarily captured by words, but which would escape irremediably when they

forgot the values of the written letters.

At the beginning of the road into the swamp they put up a sign that said MACONDO and another

larger one on the main street that said GOD EXISTS. In all the houses keys to memorizing objects

and feelings had been written. But the system demanded so much vigilance and moral strength that

many succumbed to the spell of an imaginary reality, one invented by themselves, which was less

practical for them but more comforting. Pilar Ternera was the one who contributed most to

popularize that mystification when she conceived the trick of reading the past in cards as she had

read the future before. By means of that recourse the insomniacs began to live in a world built on

the uncertain alternatives of the cards, where a father was remembered faintly as the dark man who

had arrived at the beginning of April and a mother was remembered only as the dark woman who

wore a gold ring on her left hand, and where a birth date was reduced to the last Tuesday on which a

lark sang in the laurel tree. Defeated by those practices of consolation, Jose Arcadio Buendia then

decided to build the memory machine that he had desired once in order to remember the marvelous

inventions of the gypsies. The artifact was based on the possibility of reviewing every morning, from

beginning to end, the totality of knowledge acquired during one’s life. He conceived of it as a

spinning dictionary that a person placed on the axis could operate by means of a lever, so that in a

very few hours there would pass before his eyes the notions most necessary for life. He had

succeeded in writing almost fourteen thousand entries when along the road from the swamp a

strange-looking old man with the sad sleepers’ bell appeared, carrying a bulging suitcase tied with a

rope and pulling a cart covered with black cloth. He went straight to the house of Jose Arcadio

Buendia.

Visitacion did not recognize him when she opened the door and she thought he had come with

the idea of selling something, unaware that nothing could be sold in a town that was sinking

irrevocably into the quicksand of forgetfulness. He was a decrepit man. Although his voice was also

broken by uncertainty and his hands seemed to doubt the existence of things, it was evident that he

came from the world where men could still sleep and remember.