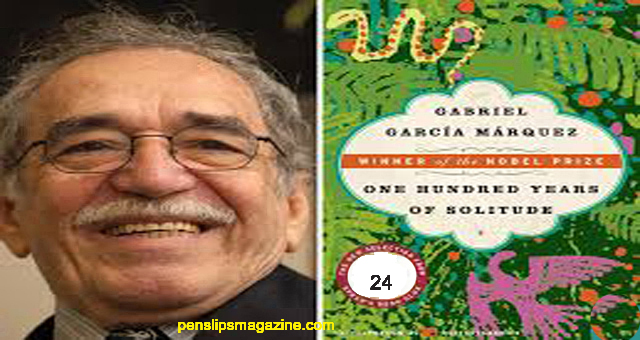

One Hundred Years of Solitde … Garcia Marquez

GABRIEL GARCIA MARQUEZ was born in Aracataca, Colombia in 1928, but he lived most of his life in Mexico and Europe. He attended the University of Bogota and later worked as staff reporter and film critic for the Colombian newspaper El Espectador. In addition to ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE, he has also written two collections of short fiction, NO ONE WRITES TO THE COLONEL and LEAF STORM.

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

Jort Areadio BoendUi

m. Cnula Iguarln

olonel Aurellano Btiendia-

m. Remcdios Moscote

-Jos6 Areadio

m-Rebeca

Aurcliano Jose

(by Pilar Ternera)

17 Aurelianos

R’emedios the Beauty

Areadio

(by Pilar Ternera)

m. Santa Sofia de la Piedad

Aurellano Segundo

m. Fernanda del Carplo

Amaranta

Jose Areadio Segundo

j_Renata

Remedios (Mane)

Aurellano

(by MauHcioBabfionla)

lose Areadio

-..Amaranta

m. Gasti

ranta Orsula

Gaston

Aurellano

(by Aurellano^

Chapter 4

24

Pietro Crespi came back to repair the pianola. Rebeca and Amaranta helped him put the strings

in order and helped him with their laughter at the mix-up of the melodies. It was extremely pleasant

and so chaste in its way that Ursula ceased her vigilance. On the eve of his departure a farewell

dance for him was improvised with the pianola and with Rebeca he put on a skillful demonstration

of modern dance, Arcadio and Amaranta matched them in grace and skill. But the exhibition was

intermpted because Pilar Ternera, who was at the door with the onlookers, had a fight, biting and

hair pulling, with a woman who had dared to comment that Arcadio had a woman’s behind. Toward

midnight Pietro Crespi took his leave with a sentimental little speech, and he promised to return

very soon. Rebeca accompanied him to the door, and having closed up the house and put out the

lamps, she went to her room to weep. It was an inconsolable weeping that lasted for several days,

the cause of which was not known even by Amaranta. Her hermetism was not odd. Although she

seemed expansive and cordial, she had a solitary character and an impenetrable heart. She was a

splendid adolescent with long and firm bones, but she still insisted on using the small wooden

rocking chair with which she had arrived at the house, reinforced many times and with the arms

gone. No one had discovered that even at that age she still had the habit of sucking her finger. That

was why she would not lose an opportunity to lock herself in the bathroom and had acquired the

habit of sleeping with her face to the wall. On rainy afternoons, embroidering with a group of

friends on the begonia porch, she would lose the thread of the conversation and a tear of nostalgia

would salt her palate when she saw the strips of damp earth and the piles of mud that the

earthworms had pushed up in the garden. Those secret tastes, defeated in the past by oranges and

rhubarb, broke out into an irrepressible urge when she began to weep. She went back to eating

earth. The first time she did it almost out of curiosity, sure that the bad taste would be the best cure

for the temptation. And, in fact, she could not bear the earth in her mouth. But she persevered,

overcome by the growing anxiety, and little by little she was getting back her ancestral appetite, the

taste of primary minerals, the unbridled satisfaction of what was the original food. She would put

handfuls of earth in her pockets, and ate them in small bits without being seen, with a confused

feeling of pleasure and rage, as she instmcted her girl friends in the most difficult needlepoint and

spoke about other men, who did not deserve the sacrifice of having one eat the whitewash on the

walls because of them. The handfuls of earth made the only man who deserved that show of

degradation less remote and more certain, as if the ground that he walked on with his fine patent

leather boots in another part of the world were transmitting to her the weight and the temperature

of his blood in a mineral savor that left a harsh aftertaste in her mouth and a sediment of peace in

her heart. One afternoon, for no reason, Amparo Moscote asked permission to see the house.

Amaranta and Rebeca, disconcerted by the unexpected visit, attended her with a stiff formality. They

showed her the remodeled mansion, they had her listen to the rolls on the pianola, and they offered

her orange marmalade and crackers. Amparo gave a lesson in dignity, personal charm, and good

manners that impressed Ursula in the few moments that she was present during the visit. After two

hours, when the conversation was beginning to wane, Amparo took advantage of Amaranta’s

distraction and gave Rebeca a letter. She was able to see the name of the Estimable Senorita Rebeca

Buendia, written in the same methodical hand, with the same green ink, and the same delicacy of

words with which the instructions for the operation of the pianola were written, and she folded the

letter with the tips of her fingers and hid it in her bosom, looking at Amparo Moscote with an

expression of endless and unconditional gratitude and a silent promise of complicity unto death.

The sudden friendship between Amparo Moscote and Rebeca Buendia awakened the hopes of

Aureliano. The memory of little Remedios had not stopped tormenting him, but he had not found a

chance to see her. When he would stroll through town with his closest friends, Magnifico Visbal and

Gerineldo Marquez—the sons of the founders of the same names—he would look for her in the

sewing shop with an anxious glance, but he saw only the older sisters. The presence of Amparo

Moscote in the house was like a premonition. “She has to come with her,” Aureliano would say to

himself in a low voice. “She has to come.” He repeated it so many times and with such conviction

that one afternoon when he was putting together a little gold fish in the work shop, he had the

certainty that she had answered his call. Indeed, a short time later he heard the childish voice, and

when he looked up his heart froze with terror as he saw the girl at the door, dressed in pink organdy

and wearing white boots.

“You can’t go in there, Remedios, Amparo Moscote said from the hall. They’re working.”

But Aureliano did not give her time to respond. He picked up the little fish by the chain that

came through its mouth and said to her.

“Come in.”

Remedios went over and asked some questions about the fish that Aureliano could not answer

because he was seized with a sudden attack of asthma. He wanted to stay beside that lily skin

forever, beside those emerald eyes, close to that voice that called him “sir” with every question,

showing the same respect that she gave her father. Melquiades was in the corner seated at the desk

scribbling indecipherable signs. Aureliano hated him. All he could do was tell Remedios that he was

going to give her the little fish and the girl was so startled by the offer that she left the workshop as

fast as she could. That afternoon Aureliano lost the hidden patience with which he had waited for a

chance to see her. He neglected his work. In several desperate efforts of concentration he willed her

to appear but Remedios did not respond. He looked for her in her sisters’ shop, behind the window

shades in her house, in her father’s office, but he found her only in the image that saturated his

private and terrible solitude. He would spend whole hours with Rebeca in the parlor listening to the

music on the pianola. She was listening to it because it was the music with which Pietro Crespi had

taught them how to dance. Aureliano listened to it simply because everything, even music, reminded

him of Remedios.