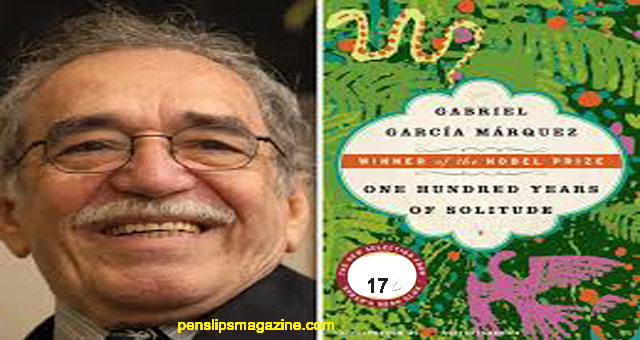

one Hundred Years of Solitude … Garcia Marquez

GABRIEL GARCIA MARQUEZ was born in Aracataca, Colombia in 1928, but he lived most of his life in Mexico and Europe. He attended the University of Bogota and later worked as staff reporter and film critic for the Colombian newspaper El Espectador. In addition to ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE, he has also written two collections of short fiction, NO ONE WRITES TO THE COLONEL and LEAF STORM.

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

Jort Areadio BoendUi

m. Cnula Iguarln

olonel Aurellano Btiendia-

m. Remcdios Moscote

-Jos6 Areadio

m-Rebeca

Aurcliano Jose

(by Pilar Ternera)

17 Aurelianos

R’emedios the Beauty

Areadio

(by Pilar Ternera)

m. Santa Sofia de la Piedad

Aurellano Segundo

m. Fernanda del Carplo

Amaranta

Jose Areadio Segundo

j_Renata

Remedios (Mane)

Aurellano

(by MauHcioBabfionla)

lose Areadio

-..Amaranta

m. Gasti

ranta Orsula

Gaston

Aurellano

(by Aurellano^

Chapter 3

17

A long time passed before

Rebeca became incorporated into the life of the family. She would sit in her small rocker sucking her

finger in the most remote corner of the house. Nothing attracted her attention except the music of

the clocks, which she would look for every half hour with her frightened eyes as if she hoped to find

it someplace in the air. They could not get her to eat for several days. No one understood why she

had not died of hunger until the Indians, who were aware of everything, for they went ceaselessly

about the house on their stealthy feet, discovered that Rebeca only liked to eat the damp earth of the

courtyard and the cake of whitewash that she picked of the walls with her nails. It was obvious that

her parents, or whoever had raised her, had scolded her for that habit because she did it secretively

and with a feeling of guilt, trying to put away supplies so that she could eat when no one was

looking. From then on they put her under an implacable watch. They threw cow gall onto the

courtyard and, mbbed hot chili on the walls, thinking they could defeat her pernicious vice with

those methods, but she showed such signs of astuteness and ingenuity to find some earth that

Ursula found herself forced to use more drastic methods. She put some orange juice and rhubarb

into a pan that she left in the dew all night and she gave her the dose the following day on an empty

stomach. Although no one had told her that it was the specific remedy for the vice of eating earth,

she thought that any bitter substance in an empty stomach would have to make the liver react.

Rebeca was so rebellious and strong in spite of her frailness that they had to tie her up like a calf to

make her swallow the medicine, and they could barely keep back her kicks or bear up under the

strange hieroglyphics that she alternated with her bites and spitting, and that, according to what the

scandalized Indians said, were the vilest obscenities that one could ever imagine in their language.

When Ursula discovered that, she added whipping to the treatment. It was never established

whether it was the rhubarb or the beatings that had effect, or both of them together, but the truth

was that in a few weeks Rebeca began to show signs of recovery. She took part in the games of

Arcadio and Amaranta, who treated her like an older sister, and she ate heartily, using the utensils

properly. It was soon revealed that she spoke Spanish with as much fluency as the Indian language,

that she had a remarkable ability for manual work, and that she could sing the waltz of the clocks

with some very funny words that she herself had invented. It did not take long for them to consider

her another member of the family. She was more affectionate to Ursula than any of her own

children had been, and she called Arcadio, and Amaranta brother and sister, Aureliano uncle, and

Jose Arcadio Buendia grandpa. So that she finally deserved, as much as the others, the name of

Rebeca Buendia, the only one that she ever had and that she bore with dignity until her death.

One night about the time that Rebeca was cured of the vice of eating earth and was brought to

sleep in the other children’s room, the Indian woman, who slept with them awoke by chance and

heard a strange, intermittent sound in the corner. She got up in alarm, thinking that an animal had

come into the room, and then she saw Rebeca in the rocker, sucking her finger and with her eyes

lighted up in the darkness like those of a cat. Terrified, exhausted by her fate, Visitacion recognized

in those eyes the symptoms of the sickness whose threat had obliged her and her brother to exile

themselves forever from an age-old kingdom where they had been prince and princess. It was the

insomnia plague.

Cataure, the Indian, was gone from the house by morning. His sister stayed because her fatalistic

heart told her that the lethal sickness would follow her, no matter what, to the farthest corner of the

earth. No one understood Visitacion’s alarm. “If we don’t ever sleep again, so much the better,” Jose

Arcadio Buendia said in good humor. “That way we can get more out of life.” But the Indian

woman explained that the most fearsome part of the sickness of insomnia was not the impossibility

of sleeping, for the body did not feel any fatigue at all, but its inexorable evolution toward a more

critical manifestation: a loss of memory. She meant that when the sick person became used to his

state of vigil, the recollection of his childhood began to be erased from his memory, then the name

and notion of tilings, and finally the identity of people and even the awareness of his own being,

Until he sank into a kind of idiocy that had no past.