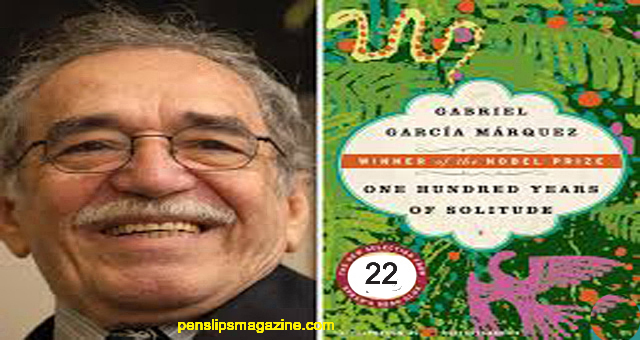

One Hundred Years of Solitude … Garcia Marquez

GABRIEL GARCIA MARQUEZ was born in Aracataca, Colombia in 1928, but he lived most of his life in Mexico and Europe. He attended the University of Bogota and later worked as staff reporter and film critic for the Colombian newspaper El Espectador. In addition to ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE, he has also written two collections of short fiction, NO ONE WRITES TO THE COLONEL and LEAF STORM.

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

Jort Areadio BoendUi

m. Cnula Iguarln

olonel Aurellano Btiendia-

m. Remcdios Moscote

-Jos6 Areadio

m-Rebeca

Aurcliano Jose

(by Pilar Ternera)

17 Aurelianos

R’emedios the Beauty

Areadio

(by Pilar Ternera)

m. Santa Sofia de la Piedad

Aurellano Segundo

m. Fernanda del Carplo

Amaranta

Jose Areadio Segundo

j_Renata

Remedios (Mane)

Aurellano

(by MauHcioBabfionla)

lose Areadio

-..Amaranta

m. Gasti

ranta Orsula

Gaston

Aurellano

(by Aurellano^

Chapter 3

22

Time mitigated his mad proposal, but it aggravated his feelings of frustration. He took refuge in

work. He resigned himself to being a womanless man for all his life in order to hide the shame of his

uselessness. In the meantime, Melquiades had printed on his plates everything that was printable in

Macondo, and he left the daguerreotype laboratory to the fantasies of Jose Arcadio Buendia who

had resolved to use it to obtain scientific proof of the existence of God. Through a complicated

process of superimposed exposures taken in different parts of the house, he was sure that sooner or

later he would get a daguerreotype of God, if He existed, or put an end once and for all to the

supposition of His existence. Melquiades got deeper into his interpretations of Nostradamus. He

would stay up until very late, suffocating in his faded velvet vest, scribbling with his tiny sparrow

hands, whose rings had lost the glow of former times. One night he thought he had found a

prediction of the future of Macondo. It was to be a luminous city with great glass houses where

there was no trace remaining of the race of the Buendia. “It’s a mistake,” Jose Arcadio Buendia

thundered. “They won’t be houses of glass but of ice, as I dreamed, and there will always be a

Buendia, per omnia secula seculorumP Ursula fought to preserve common sense in that extravagant

house, having broadened her business of little candy animals with an oven that went all night turning

out baskets and more baskets of bread and a prodigious variety of puddings, meringues, and cookies,

which disappeared in a few hours on the roads winding through the swamp. She had reached an age

where she had a right to rest, but she was nonetheless more and more active. So busy was she in her

prosperous enterprises that one afternoon she looked distractedly toward the courtyard while the

Indian woman helped her sweeten the dough and she saw two unknown and beautiful adolescent

girls doing frame embroidery in the light of the sunset. They were Rebeca and Amaranta. As soon as

they had taken off the mourning clothes for their grandmother, which they wore with inflexible

rigor for three years, their bright clothes seemed to have given them a new place in the world.

Rebeca, contrary to what might have been expected, was the more beautiful. She had a light

complexion, large and peaceful eyes, and magical hands that seemed to work out the design of the

embroidery with invisible threads. Amaranta, the younger, was somewhat graceless, but she had the

natural distinction, the inner tightness of her dead grandmother. Next to them, although he was

already revealing the physical drive of his father, Arcadio looked like a child. He set about learning

the art of silverwork with Aureliano, who had also taught him how to read and write. Ursula

suddenly realized that the house had become full of people, that her children were on the point of

marrying and having children, and that they would be obliged to scatter for lack of space. Then she

took out the money she had accumulated over long years of hard labor, made some arrangements

with her customers, and undertook the enlargement of the house. She had a formal parlor for visits

built, another one that was more comfortable and cool for daily use, a dining room with a table with

twelve places where the family could sit with all of their guests, nine bedrooms with windows on the

courtyard and a long porch protected from the heat of noon by a rose garden with a railing on

which to place pots of ferns and begonias. She had the kitchen enlarged to hold two ovens. The

granary where Pilar Ternera had read Jose Arcadio’s future was tom down and another twice as large

built so that there would never be a lack of food in the house. She had baths built is the courtyard in

the shade of the chestnut tree, one for the women and another for the men, and in the rear a large

stable, a fenced-in chicken yard, a shed for the milk cows, and an aviary open to the four winds so

that wandering birds could roost there at their pleasure. Followed by dozens of masons and

carpenters, as if she had contracted her husband’s hallucinating fever, Ursula fixed the position of

light and heat and distributed space without the least sense of its limitations. The primitive building

of the founders became filled with tools and materials, of workmen exhausted by sweat, who asked

everybody please not to molest them, exasperated by the sack of bones that followed them

everywhere with its dull rattle. In that discomfort, breathing quicklime and tar, no one could see very

well how from the bowels of the earth there was rising not only the largest house is the town, but

the most hospitable and cool house that had ever existed in the region of the swamp. Jose Buendia,

trying to surprise Divine Providence in the midst of the cataclysm, was the one who least

understood it. The new house was almost finished when Ursula drew him out of his chimerical

world in order to inform him that she had an order to paint the front blue and not white as they had

wanted. She showed him the official document. Jose Arcadio Buendia, without understanding what

his wife was talking about, deciphered the signature.

“Who is this fellow?” he asked:

“The magistrate,” Ursula answered disconsolately. They say he’s an authority sent by the

government.”

Don Apolinar Moscote, the magistrate, had arrived in Macondo very quietly. He put up at the

Hotel Jacob—built by one of the first Arabs who came to swap knickknacks for macaws—and on

the following day he rented a small room with a door on the street two blocks away from the

Buendia house. He set up a table and a chair that he had bought from Jacob, nailed up on the wall

the shield of the republic that he had brought with him, and on the door he painted the sign:

Magistrate. His first order was for all the houses to be painted blue in celebration of the anniversary

of national independence. Jose Arcadio Buendia, with the copy of the order in his hand, found him

taking his nap in a hammock he had set up in the narrow office. “Did you write this paper?” he

asked him. Don Apolinar Moscote, a mature man, timid, with a ruddy complexion, said yes. “By

what right?” Jose Arcadio Buendia asked again. Don Apolinar Moscote picked up a paper from the

drawer of the table and showed it to him. “I have been named magistrate of this town.” Jose

Arcadio Buendia did not even look at the appointment.

“In this town we do not give orders with pieces of paper,” he said without losing his calm. “And

so that you know it once and for all, we don’t need any judge here because there’s nothing that

needs judging.”

Facing Don Apolinar Moscote, still without raising his voice, he gave a detailed account of how

they had founded the village, of how they had distributed the land, opened the roads, and

introduced the improvements that necessity required without having bothered the government and

without anyone having bothered them. “We are so peaceful that none of us has died even of a

natural death,” he said. “You can see that we still don’t have any cemetery.” No once was upset that

the government had not helped them. On the contrary, they were happy that up until then it had let

them grow in peace, and he hoped that it would continue leaving them that way, because they had

not founded a town so that the first upstart who came along would tell them what to do. Don

Apolinar had put on his denim jacket, white like his trousers, without losing at any moment the

elegance of his gestures.

“So that if you want to stay here like any other ordinary citizen, you’re quite welcome,” Jose

Arcadio Buendla concluded. “But if you’ve come to cause disorder by making the people paint their

houses blue, you can pick up your junk and go back where you came from. Because my house is

going to be white, white, like a dove.”

Don Apolinar Moscote turned pale. He took a step backward and tightened his jaws as he said

with a certain affliction:

“I must warn you that I’m armed.”

Jose Arcadio Buendla did not know exactly when his hands regained the useful strength with

which he used to pull down horses. He grabbed Don Apolinar Moscote by the lapels and lifted him

up to the level of his eyes.

“I’m doing this,” he said, “because I would rather carry you around alive and not have to keep

carrying you around dead for the rest of my life.”