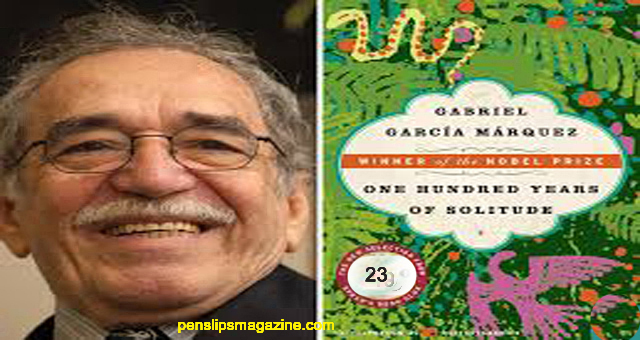

One Hundred Years of Solitude … Garcia Marquez

GABRIEL GARCIA MARQUEZ was born in Aracataca, Colombia in 1928, but he lived most of his life in Mexico and Europe. He attended the University of Bogota and later worked as staff reporter and film critic for the Colombian newspaper El Espectador. In addition to ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE, he has also written two collections of short fiction, NO ONE WRITES TO THE COLONEL and LEAF STORM.

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

Jort Areadio BoendUi

m. Cnula Iguarln

olonel Aurellano Btiendia-

m. Remcdios Moscote

-Jos6 Areadio

m-Rebeca

Aurcliano Jose

(by Pilar Ternera)

17 Aurelianos

R’emedios the Beauty

Areadio

(by Pilar Ternera)

m. Santa Sofia de la Piedad

Aurellano Segundo

m. Fernanda del Carplo

Amaranta

Jose Areadio Segundo

j_Renata

Remedios (Mane)

Aurellano

(by MauHcioBabfionla)

lose Areadio

-..Amaranta

m. Gasti

ranta Orsula

Gaston

Aurellano

(by Aurellano^

Chapter 3

23

In that way he carried him through the middle of the street, suspended by the lapels, until he put

him down on his two feet on the swamp road. A week later he was back with six barefoot and

ragged soldiers, armed with shotguns, and an oxcart in which his wife and seven daughters were

traveling. Two other carts arrived later with the furniture, the baggage, and the household utensils.

He settled his family in the Hotel Jacob, while he looked for a house, and he went back to open his

office under the protection of the soldiers. The founders of Macondo, resolving to expel the

invaders, went with their older sons to put themselves at the disposal of Jose Arcadio Buendla. But

he was against it, as he explained, because it was not manly to make trouble for someone in front of

his family, and Don Apolinar had returned with his wife and daughters. So he decided to resolve the

situation in a pleasant way.

Aureliano went with him. About that time he had begun to cultivate the black mustache with

waxed tips and the somewhat stentorian voice that would characterize him in the war. Unarmed,

without paying any attention to the guards, they went into the magistrate’s office. Don Apolinar

Moscote did not lose his calm. He introduced them to two of his daughters who happened to be

there: Amparo, sixteen, dark like her mother, and Remedios, only nine, a pretty little girl with lily-

colored skin and green eyes. They were gracious and well-mannered. As soon as the men came in,

before being introduced, they gave them chairs to sit on. But they both remained standing.

“Very well, my friend,” Jose Arcadio Buendla said, “you may stay here, not because you have

those bandits with shotguns at the door, but out of consideration for your wife and daughters.”

Don Apolinar Moscote was upset, but Jose Arcadio Buendla did not give him time to reply. “We

only make two conditions,” he went on. “The first: that everyone can paint his house the color he

feels like. The second: that the soldiers leave at once. We will guarantee order for you.” The

magistrate raised his right hand with all the fingers extended.

“Your word of honor?”

“The word of your enemy,” Jose Arcadio Buendla said. And he added in a bitter tone: “Because I

must tell you one thing: you and I are still enemies.”

The soldiers left that same afternoon. A few days later Jose Arcadio Buendla found a house for

the magistrate’s family. Everybody was at peace except Aureliano. The image of Remedios, the

magistrate’s younger daughter, who, because of her age, could have been his daughter, kept paining

him in some part of his body. It was a physical sensation that almost bothered him when he walked,

like a pebble in his shoe.

Chapter 4

THE NEW HOUSE, white, like a dove, was inaugurated with a dance. Ursula had got that idea from

the afternoon when she saw Rebeca and Amaranta changed into adolescents, and it could almost

have been said that the main reason behind the construction was a desire to have a proper place for

the girls to receive visitors. In order that nothing would be lacking in splendor she worked like a

galley slave as the repairs were under way, so that before they were finished she had ordered costly

necessities for the decorations, the table service, and the marvelous invention that was to arouse the

astonishment of the town and the jubilation of the young people: the pianola. They delivered it

broken down, packed in several boxes that were unloaded along with the Viennese furniture, the

Bohemian crystal, the table service from the Indies Company, the tablecloths from Holland, and a

rich variety of lamps and candlesticks, hangings and drapes. The import house sent along at its own

expense an Italian expert, Pietro Crespi, to assemble and tune the pianola, to instruct the purchasers

in its functioning, and to teach them how to dance the latest music printed on its six paper rolls.

Pietro Crespi was young and blond, the most handsome and well mannered man who had ever

been seen in Macondo, so scrupulous in his dress that in spite of the suffocating heat he would work

in his brocade vest and heavy coat of dark cloth. Soaked in sweat, keeping a reverent distance from

the owners of the house, he spent several weeks shut up is the parlor with a dedication much like

that of Aureliano in his silverwork. One morning, without opening the door, without calling anyone

to witness the miracle, he placed the first roll in the pianola and the tormenting hammering and the

constant noise of wooden lathings ceased in a silence that was startled at the order and neatness of

the music. They all ran to the parlor. Jose Arcadio Buendia was as if stmck by lightning, not because

of the beauty of the melody, but because of the automatic working of the keys of the pianola, and he

set up Melquiades’ camera with the hope of getting a daguerreotype of the invisible player. That day

the Italian had lunch with them. Rebeca and Amaranta, serving the table, were intimidated by the

way in which the angelic man with pale and ringless hands manipulated the utensils. In the living

room, next to the parlor, Pietro Crespi taught them how to dance. He showed them the steps

without touching them, keeping time with a metronome, under the friendly eye of Ursula, who did

not leave the room for a moment while her daughters had their lesson. Pietro Crespi wore special

pants on those days, very elastic and tight, and dancing slippers, “You don’t have to worry so

much,” Jose Arcadio Buendia told her. “The man’s a fairy.” But she did not leave off her vigilance

until the apprenticeship was over and the Italian left Macondo. Then they began to organize the

party. Ursula drew up a strict guest list, in which the only ones invited were the descendants of the

founders, except for the family of Pilar Ternera, who by then had had two more children by

unknown fathers. It was truly a high-class list, except that it was determined by feelings of

friendship, for those favored were not only the oldest friends of Jose Arcadio Buendia’s house since

before they undertook the exodus and the founding of Macondo, but also their sons and grandsons,

who were the constant companions of Aureliano and Arcadio since infancy, and their daughters,

who were the only ones who visited the house to embroider with Rebeca and Amaranta. Don

Apolinar Moscote, the benevolent ruler whose activity had been reduced to the maintenance from

his scanty resources of two policemen armed with wooden clubs, was a figurehead. In older to

support the household expenses his daughters had opened a sewing shop, where they made felt

flowers as well as guava delicacies, and wrote love notes to order. But in spite of being modest and

hard-working, the most beautiful girls in Iowa, and the most skilled at the new dances, they did not

manage to be considered for the party.

While Ursula and the girls unpacked furniture, polished silverware, and hung pictures of maidens

in boats full of roses, which gave a breath of new life to the naked areas that the masons had built,

Jose Arcadio Buendia stopped his pursuit of the image of God, convinced of His nonexistence, and

he took the pianola apart in order to decipher its magical secret. Two days before the party,

swamped in a shower of leftover keys and hammers, bungling in the midst of a mix-up of strings

that would unroll in one direction and roll up again in the other, he succeeded in a fashion in putting

the instmment back together. There had never been as many surprises and as much dashing about as

in those days, but the new pitch lamps were lighted on the designated day and hour. The house was

opened, still smelling of resin and damp whitewash, and the children and grandchildren of the

founders saw the porch with ferns and begonias, the quiet rooms, the garden saturated with the

fragrance of the roses, and they gathered together in the parlor, facing the unknown invention that

had been covered with a white sheet. Those who were familiar with the piano, popular in other

towns in the swamp, felt a little disheartened, but more bitter was Ursula’s disappointment when she

put in the first roll so that Amaranta and Rebeca could begin the dancing and the mechanism did

not work. Melquiades, almost blind by then, crumbling with decrepitude, used the arts of his

timeless wisdom in an attempt to fix it. Finally Jose Arcadio Buendia managed, by mistake, to move

a device that was stuck and the music came out, first in a burst and then in a flow of mixed-up

notes. Beating against the strings that had been put in without order or concert and had been tuned

with temerity, the hammers let go. But the stubborn descendants of the twenty-one intrepid people

who plowed through the mountains in search of the sea to the west avoided the reefs of the melodic

mix-up and the dancing went on until dawn.