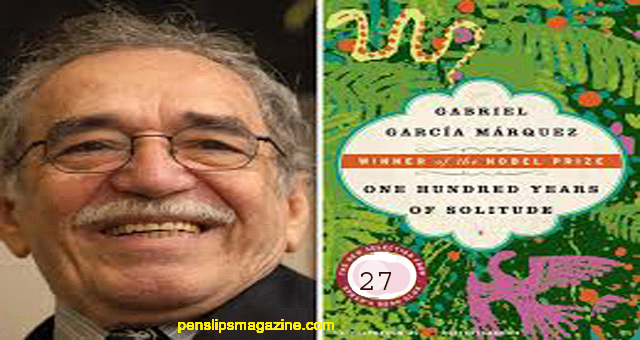

One Hundred Years of Solitude … Garcia Marquez

GABRIEL GARCIA MARQUEZ was born in Aracataca, Colombia in 1928, but he lived most of his life in Mexico and Europe. He attended the University of Bogota and later worked as staff reporter and film critic for the Colombian newspaper El Espectador. In addition to ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE, he has also written two collections of short fiction, NO ONE WRITES TO THE COLONEL and LEAF STORM.

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

Jort Areadio BoendUi

m. Cnula Iguarln

olonel Aurellano Btiendia-

m. Remcdios Moscote

-Jos6 Areadio

m-Rebeca

Aurcliano Jose

(by Pilar Ternera)

17 Aurelianos

R’emedios the Beauty

Areadio

(by Pilar Ternera)

m. Santa Sofia de la Piedad

Aurellano Segundo

m. Fernanda del Carplo

Amaranta

Jose Areadio Segundo

j_Renata

Remedios (Mane)

Aurellano

(by MauHcioBabfionla)

lose Areadio

-..Amaranta

m. Gasti

ranta Orsula

Gaston

Aurellano

(by Aurellano^

27

The house became full of loves Aureliano expressed it in poetry that had no beginning or end.

He would write it on the harsh pieces of parchment that Melquiades gave him, on the bathroom

walls, on the skin of his arms, and in all of it Remedios would appear transfigured: Remedios in the

soporific air of two in the afternoon, Remedios in the soft breath of the roses, Remedios in the

water-clock secrets of the moths, Remedios in the steaming morning bread, Remedios everywhere

and Remedios forever. Rebeca waited for her love at four in the afternoon, embroidering by the

window. She knew that the mailman’s mule arrived only every two weeks, but she always waited for

him, convinced that he was going to arrive on some other day by mistake. It happened quite the

opposite: once the mule did not come on the usual day. Mad with desperation, Rebeca got up in the

middle of the night and ate handfuls of earth in the garden with a suicidal drive, weeping with pain

and fury, chewing tender earthworms and chipping her teeth on snail shells. She vomited until dawn.

She fell into a state of feverish prostration, lost consciousness, and her heart went into a shameless

delirium. Ursula, scandalized, forced the lock on her trunk and found at the bottom, tied together

with pink ribbons, the sixteen perfumed letters and the skeletons of leaves and petals preserved in

old books and the dried butterflies that turned to powder at the touch.

Aureliano was the only one capable of understanding such desolation. That afternoon, while

Ursula was trying to rescue Rebeca from the slough of delirium, he went with Magnifico Visbal and

Gerineldo Marquez to Catarino’s store. The establishment had been expanded with a gallery of

wooden rooms where single women who smelled of dead flowers lived. A group made up of an

accordion and dmms played the songs of Francisco the Man, who had not been seen in Macondo

for several years. The three friends drank fermented cane juice. Magnifico and Gerineldo,

contemporaries of Aureliano but more skilled in the ways of the world, drank methodically with the

women seated on their laps. One of the women, withered and with goldwork on her teeth, gave

Aureliano a caress that made him shudder. He rejected her. He had discovered that the more he

drank the more he thought about Remedios, but he could bear the torture of his recollections better.

He did not know exactly when he began to float. He saw his friends and the women sailing in a

radiant glow, without weight or mass, saying words that did not come out of their mouths and

making mysterious signals that did not correspond to their expressions. Catarino put a hand on his

shoulder and said to him: “It’s going on eleven.” Aureliano turned his head, saw the enormous

disfigured face with a felt flower behind the ear, and then he lost his memory, as during the times of

forgetfulness, and he recovered it on a strange dawn and in a room that was completely foreign,

where Pilar Ternera stood in her slip, barefoot, her hair down, holding a lamp over him, starded

with disbelief.

“Aureliano!”

Aureliano checked his feet and raised his head. He did not know how he had come there, but he

knew what his aim was, because he had carried it hidden since infancy in an inviolable backwater of

his heart.

“I’ve come to sleep with you,” he said.

His clothes were smeared with mud and vomit. Pilar Ternera, who lived alone at that time with

her two younger children, did not ask him any quesdons. She took him to the bed. She cleaned his

face with a damp cloth, took of his clothes, and then got completely undressed and lowered the

mosquito netting so that her children would not see them if they woke up. She had become dred of

waiting for the man who would stay, of the men who left, of the countless men who missed the road

to her house, confused by the uncertainty of the cards. During the wait her skin had become

wrinkled, her breasts had withered, the coals of her heart had gone out. She felt for Aureliano in the

darkness, put her hand on his stomach and kissed him on the neck with a maternal tenderness. “My

poor child,” she murmured. Aureliano shuddered. With a calm skill, without the slightest misstep, he

left his accumulated grief behind and found Remedios changed into a swamp without horizons,

smelling of a raw animal and recendy ironed clothes. When he came to the surface he was weeping.

First they were involuntary and broken sobs. Then he emptied himself out in an unleashed flow,

feeling that something swollen and painful had burst inside of him. She waited, snatching his head

with the tips of her fingers, until his body got rid of the dark material that would not let him live.

They Pilar Ternera asked him: “Who is it?” And Aureliano told her. She let out a laugh that in other

times frightened the doves and that now did not even wake up the children. “You’ll have to raise her

first,” she mocked, but underneath the mockery Aureliano found a reservoir of understanding.

When he went out of the room, leaving behind not only his doubts about his virility but also the

bitter weight that his heart had borne for so many months. Pilar Ternera made him a spontaneous

promise.

“I’m going to talk to the girl,” she told him, “and you’ll see what I’ll serve her on the tray.”

She kept her promise. But it was a bad moment, because the house had lost its peace of former

days. When she discovered Rebeca’s passion, which was impossible to keep secret because of her

shouts, Amaranta suffered an attack of fever. She also suffered from the barb of a lonely love. Shut

up in the bathroom, she would release herself from the torment of a hopeless passion by writing

feverish letters, which she finally hid in the bottom of her trunk. Ursula barely had the strength to

take care of the two sick girls. She was unable, after prolonged and insidious interrogations, to

ascertain the causes of Amaranta’s prostration. Finally, in another moment of inspiration, she forced

the lock on the trunk and found the letters tied with a pink ribbon, swollen with fresh lilies and still

wet with tears, addressed and never sent to Pietro Crespi. Weeping with rage, she cursed the day that

it had occurred to her to buy the pianola, and she forbade the embroidery lessons and decreed a

kind of mourning with no one dead which was to be prolonged until the daughters got over their

hopes. Useless was the intervention of Jose Arcadio Buendia, who had modified his first impression

of Pietro Crespi and admired his ability in the manipulation of musical machines. So that when Pilar

Ternera told Aureliano that Remedios had decided on marriage, he could see that the news would

only give his parents more trouble. Invited to the parlor for a formal interview, Jose Arcadio

Buendia and Ursula listened stonily to their son’s declaration. When he learned the name of the

fiancee, however, Jose Arcadio Buendia grew red with indignation. “Love is a disease,” he

thundered. “With so many pretty and decent girls around, the only tiling that occurs to you is to get

married to the daughter of our enemy.” But Ursula agreed with the choice. She confessed her

affection for the seven Moscote sisters, for their beauty, their ability for work, their modesty, and

their good manners, and she celebrated her son’s prudence. Conquered by his wife’s enthusiasm,

Jose Arcadio Buendia then laid down one condition: Rebeca, who was the one he wanted, would

marry Pietro Crespi. Ursula would take Amaranta on a trip to the capital of the province when she

had time, so that contact with different people would alleviate her disappointment. Rebeca got her

health back just as soon as she heard of the agreement, and she wrote her fiance a jubilant letter that

she submitted to her parents’ approval and put into the mail without the use of any intermediaries.

Amaranta pretended to accept the decision and little by little she recovered from her fevers, but she

promised herself that Rebeca would marry only over her dead body.

The following Saturday Jose Arcadio Buendia put on his dark suit, his celluloid collar, and the

deerskin boots that he had worn for the first time the night of the party, and went to ask for the

hand of Remedios Moscote. The magistrate and his wife received him, pleased and worried at the

same time, for they did not know the reason for the unexpected visit, and then they thought that he

was confused about the name of the intended bride. In order to remove the mistake, the mother

woke Remedios up and carried her into the living room, still drowsy from sleep. They asked her if it

was tme that she had decided to get married, and she answered, whimpering, that she only wanted

them to let her sleep. Jose Arcadio Buendia, understanding the distress of the Moscotes, went to

clear things up with Aureliano. When he returned, the Moscotes had put on formal clothing, had

rearranged the furniture and put fresh flowers in the vases, and were waiting in the company of their

older daughters. Overwhelmed by the unpleasantness of the occasion and the bothersome hard

collar, Jose Arcadio Buendia confirmed the fact that Remedios, indeed, was the chosen one. “It

doesn’t make sense,” Don Apolinar Moscote said with consternation. “We have six other daughters,

all unmarried, and at an age where they deserve it, who would be delighted to be the honorable wife

of a gentleman as serious and hard-working as your son, and Aurelito lays his eyes precisely on the

one who still wets her bed.” His wife, a well-preserved woman with afflicted eyelids and expression,

scolded his mistake. When they finished the fruit punch, they willingly accepted Aureliano’s

decision. Except that Senora Moscote begged the favor of speaking to Ursula alone. Intrigued,

protesting that they were involving her in men’s affairs, but really feeling deep emotion, Ursula went

to visit her the next day. A half hour later she returned with the news that Remedios had not

reached puberty. Aureliano did not consider that a serious barrier. He had waited so long that he

could wait as long as was necessary until his bride reached the age of conception.