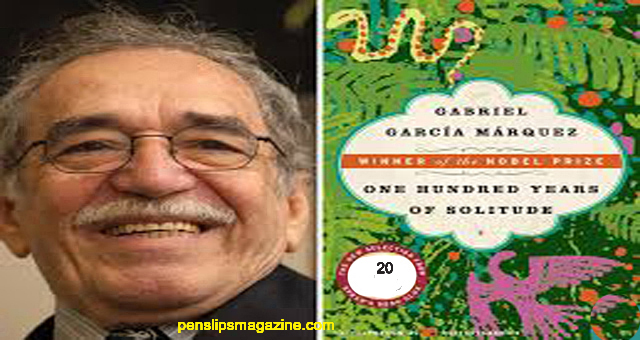

One Hundred Years of Solitude … Garcia Marquez

GABRIEL GARCIA MARQUEZ was born in Aracataca, Colombia in 1928, but he lived most of his life in Mexico and Europe. He attended the University of Bogota and later worked as staff reporter and film critic for the Colombian newspaper El Espectador. In addition to ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE, he has also written two collections of short fiction, NO ONE WRITES TO THE COLONEL and LEAF STORM.

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

Jort Areadio BoendUi

m. Cnula Iguarln

olonel Aurellano Btiendia-

m. Remcdios Moscote

-Jos6 Areadio

m-Rebeca

Aurcliano Jose

(by Pilar Ternera)

17 Aurelianos

R’emedios the Beauty

Areadio

(by Pilar Ternera)

m. Santa Sofia de la Piedad

Aurellano Segundo

m. Fernanda del Carplo

Amaranta

Jose Areadio Segundo

j_Renata

Remedios (Mane)

Aurellano

(by MauHcioBabfionla)

lose Areadio

-..Amaranta

m. Gasti

ranta Orsula

Gaston

Aurellano

(by Aurellano^

Chapter 3

20

Jose Arcadio Buendia found him

Sitting in the living room fanning himself with a patched black hat as he read with compassionate

Attention the signs pasted to the walls. He greeted him with a broad show of affection, afraid that he

had known him at another time and that he did not remember him now. But the visitor was aware

of his falseness. He felt himself forgotten, not with the irremediable forgetfulness of the heart, but

With a different kind of forgetfulness, which was more cmel and irrevocable and which he knew very

Well because it was the forgetfulness of death. Then he understood. He opened the suitcase

Crammed with indecipherable objects and from among then he took out a little case with many

Flasks. He gave Jose Arcadio Buendia a drink of a gentle color and the light went on in his memory.

His eyes became moist from weeping even before he noticed himself in an absurd living room

Where objects were labeled and before he was ashamed of the solemn nonsense written on the walls,

and even before he recognized the newcomer with a dazzling glow of joy. It was Melquiades.

While Macondo was celebrating the recovery of its memory, Jose Arcadio Buendia and

Melquiades dusted off their old friendship. The gypsy was inclined to stay in the town. He really had

been through death, but he had returned because he could not bear the solitude. Repudiated by his

Tribe, having lost all of his supernatural faculties because of his faithfulness to life, he decided to take

Refuge in that corner of the world which had still not been discovered by death, dedicated to the

Operation of a daguerreotype laboratory. Jose Arcadio Buendia had never heard of that invention.

But when he saw himself and his whole family fastened onto a sheet of iridescent metal for an

Eternity, he was mute with stupefaction. That was the date of the oxidized daguerreotype in which

Jose Arcadio Buendia appeared with his brisdy and graying hair, his card board collar attached to his

shirt by a copper button, and an expression of startled solemnity, whom Ursula described, dying

with laughter, as a “frightened general.” Jose Arcadio Buendia was, in fact, frightened on that dear

December morning when the daguerreotype was made, for he was thinking that people were slowly

wearing away while his image would endure an a metallic plaque. Through a curious reversal of

custom, it was Ursula who got that idea out of his head, as it was also she who forgot her ancient

bitterness and decided that Melquiades would stay on in the house, although she never permitted

them to make a daguerreotype of her because (according to her very words) she did not want to

survive as a laughingstock for her grandchildren. That morning she dressed the children in their best

clothes, powdered their faces, and gave a spoonful of marrow syrup to each one so that they would

all remain absolutely motionless during the nearly two minutes in front of Melquiades fantastic

camera. In the family daguerreotype, the only one that ever existed, Aureliano appeared dressed in

black velvet between Amaranta and Rebeca. He had the same languor and the same clairvoyant look

that he would have years later as he faced the firing squad. But he still had not sensed the

premonition of his fate. He was an expert silversmith, praised all over the swampland for the

delicacy of his work. In the workshop, which he shared with Melquiades’ mad laboratory, he could

barely be heard breathing. He seemed to be taking refuge in some other time, while his father and

the gypsy with shouts interpreted the predictions of Nostradamus amidst a noise of flasks and trays

and the disaster of spilled acids and silver bromide that was lost in the twists and turns it gave at

every instant. That dedication to his work, the good judgment with which he directed his attention,

had allowed Aureliano to earn in a short time more money than Ursula had with her delicious candy

fauna, but everybody thought it strange that he was now a full-grown man and had not known a

woman. It was true that he had never had one.