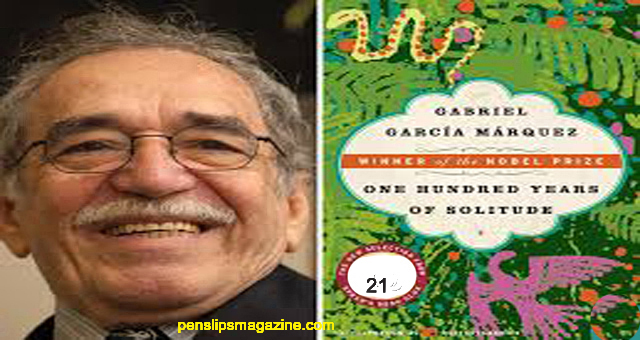

One Hundred Years of Solitude … Garcia Marquez

GABRIEL GARCIA MARQUEZ was born in Aracataca, Colombia in 1928, but he lived most of his life in Mexico and Europe. He attended the University of Bogota and later worked as staff reporter and film critic for the Colombian newspaper El Espectador. In addition to ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE, he has also written two collections of short fiction, NO ONE WRITES TO THE COLONEL and LEAF STORM.

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

Jort Areadio BoendUi

m. Cnula Iguarln

olonel Aurellano Btiendia-

m. Remcdios Moscote

-Jos6 Areadio

m-Rebeca

Aurcliano Jose

(by Pilar Ternera)

17 Aurelianos

R’emedios the Beauty

Areadio

(by Pilar Ternera)

m. Santa Sofia de la Piedad

Aurellano Segundo

m. Fernanda del Carplo

Amaranta

Jose Areadio Segundo

j_Renata

Remedios (Mane)

Aurellano

(by MauHcioBabfionla)

lose Areadio

-..Amaranta

m. Gasti

ranta Orsula

Gaston

Aurellano

(by Aurellano^

Chapter 3

21

Several months later saw the return of Francisco the Man, as ancient vagabond who was almost

two hundred years old and who frequently passed through Macondo distributing songs that he

composed himself. In them Francisco the Man told in great detail the things that had happened in

the towns along his route, from Manaure to the edge of the swamp, so that if anyone had a message

to send or an event to make public, he would pay him two cents to include it in his repertory. That

was how Ursula learned of the death of her mother, as a simple consequence of listening to the

songs in the hope that they would say something about her son Jose Arcadio. Francisco the Man,

called that because he had once defeated the devil in a duel of improvisation, and whose real name

no one knew, disappeared from Macondo during the insomnia plague and one night he appeared

suddenly in Catarino’s store. The whole town went to listen to him to find out what had happened

in the world. On that occasion there arrived with him a woman who was so fat that four Indians had

to carry her in a rocking chair, and an adolescent mulatto girl with a forlorn look who protected her

from the sun with an umbrella. Aureliano went to Catarino’s store that night. He found Francisco

the Man, like a monolithic chameleon, sitting in the midst of a circle of bystanders. He was singing

the news with his old, out-of-tune voice, accompanying himself with the same archaic accordion that

Sir Walter Raleigh had given him in the Guianas and keeping time with his great walking feet that

were cracked from saltpeter. In front of a door at the rear through which men were going and

coming, the matron of the rocking chair was sitting and fanning herself in silence. Catarino, with a

felt rose behind his ear, was selling the gathering mugs of fermented cane juice, and he took

advantage of the occasion to go over to the men and put his hand on them where he should not

have. Toward midnight the heat was unbearable. Aureliano listened to the news to the end without

hearing anything that was of interest to his family. He was getting ready to go home when the

matron signaled him with her hand.

“You go in too.” she told him. “It only costs twenty cents.”

Aureliano threw a coin into the hopper that the matron had in her lap and went into the room

without knowing why. The adolescent mulatto girl, with her small bitch’s teats, was naked on the

bed. Before Aureliano sixty-three men had passed through the room that night. From being used so

much, kneaded with sweat and sighs, the air in the room had begun to turn to mud. The girl took

off the soaked sheet and asked Aureliano to hold it by one side. It was as heavy as a piece of canvas.

They squeezed it, twisting it at the ends until it regained its natural weight. They turned over the mat

and the sweat came out of the other side. Aureliano was anxious for that operation never to end. He

knew the theoretical mechanics of love, but he could not stay on his feet because of the weakness of

his knees, and although he had goose pimples on his burning skin he could not resist the urgent

need to expel the weight of his bowels. When the girl finished fixing up the bed and told him to get

undressed, he gave her a confused explanation: “They made me come in. They told me to throw

twenty cents into the hopper and hurry up.” The girl understood his confusion. “If you throw in

twenty cents more when you go out, you can stay a little longer,” she said softly. Aureliano got

undressed, tormented by shame, unable to get rid of the idea that-his nakedness could not stand

comparison with that of his brother. In spite of the girl’s efforts he felt more and more indifferent

and terribly alone. “I’ll throw in other twenty cents,” he said with a desolate voice. The girl thanked

him in silence. Her back was raw. Her skin was stuck to her ribs and her breathing was forced

because of an immeasurable exhaustion. Two years before, far away from there, she had fallen asleep

without putting out the candle and had awakened surrounded by flames. The house where she lived

with the grandmother who had raised her was reduced to ashes. Since then her grandmother carried

her from town to town, putting her to bed for twenty cents in order to make up the value of the

burned house. According to the girl’s calculations, she still had ten years of seventy men per night,

because she also had to pay the expenses of the trip and food for both of them as well as the pay of

the Indians who carried the rocking chair. When the matron knocked on the door the second time,

Aureliano left the room without having done anything, troubled by a desire to weep. That night he

could not sleep, thinking about the girl, with a mixture of desire and pity. He felt an irresistible need

to love her and protect her. At dawn, worn out by insomnia and fever, he made the calm decision to

marry her in order to free her from the despotism of her grandmother and to enjoy all the nights of

satisfaction that she would give the seventy men. But at ten o’clock in the morning, when he reached

Catarino’s store, the girl had left town.